Home, Birth, Dixon, Evanston, MIT, Army, Lockheed, Urbana, Research, Digigraphics, Cabin John, Bell Labs, Leisure World, Riderwood, Search

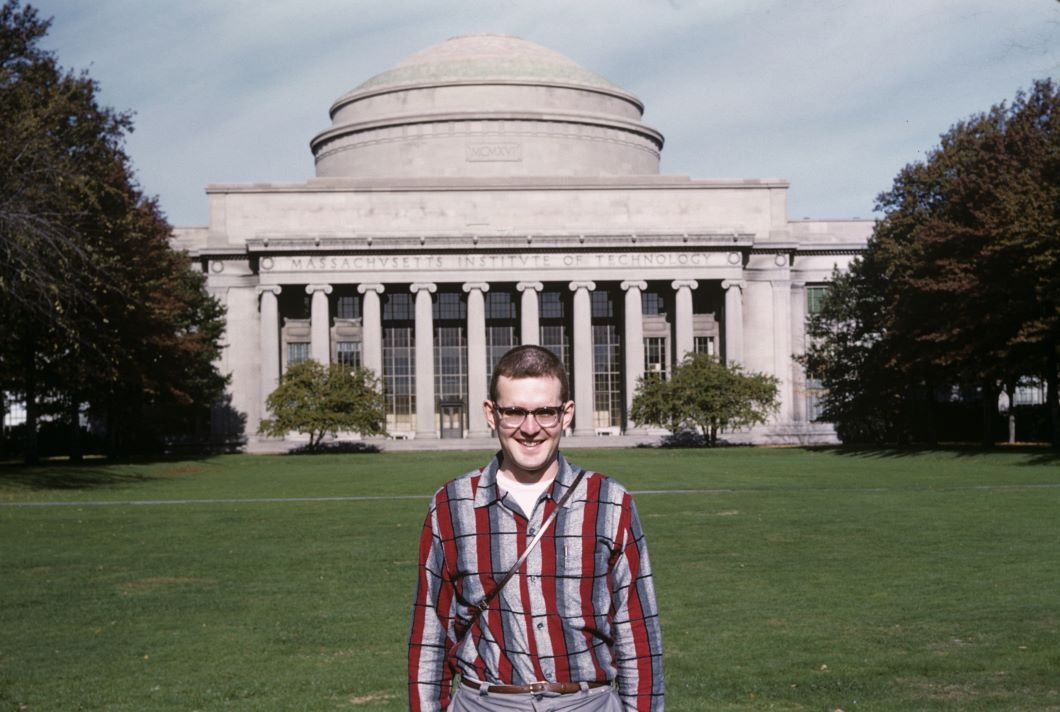

Cambridge (MIT

1954-1958)

Now, the hard part. My mother and grandfather were set on me going to MIT. It

was a given that I was to go there, so I did. We lived in Evanston with

Northwestern, and most of my friends went there. Some friends went 150 miles

south to the University of Illinois. We never visited any college. I took a

tour of Northwestern Engineering School but never got any impression of campus

life or entertained any thought of going there. MIT was a given, not a choice.

The 1936 birth year class was small, so it was not hard to get in. If you had a

slide rule, you're in.

I knew my way around Chicago and New York but

had not seen Boston. What a shock. What a delight. A perfect city to be a

student.

However, I was not ready to be a student at

MIT. I was way too immature, way too unworldly, way too shy, and unprepared for

MIT. There are only two kinds of students who thrive at MIT: brilliant

kids with high IQs and mature rich kids who are well-traveled and can afford

tutors. I was neither. I came in inadequately prepared for life -- academically

and socially.

Here is a fellow student's nostalgic

description of my stay. I remember these times as he describes them. https://thetech.com/2015/04/02/elander-v135-n9

Looking back, I realize that my life at MIT

was horrible. My experience was not unusual (my cousin committed

suicide in his dorm there). I had been groomed to go

to MIT since I was little. I had no choice, and I had no life.

When I first

arrived, I was assigned a room in the East Campus dorms. Mom insisted I was

going to pledge a fraternity. They were across the river, and I did not have

the slightest interest in or the social skills to enter them. I met every

friend I had at MIT in that first week in the dorm. I lived in Hayden 302 all 4 years and never set foot in any other living or

social place at MIT. There are dozens of colleges in the area. Except for some library work up the street at Harvard, I never visited any

of them.

I did not participate in any social activity

in the dorms or school and did not attend church or continue with scouts. I had

been suffering from depression and low self-esteem

since 7th grade and through High School. Going to MIT made all this

worse.

I started in Electrical Engineering like my

uncle and what seemed reasonable from my hobbies. At the end of the first year,

it was obvious that I could not handle the math, so I switched to Aeronautical

Engineering. It was a wrong choice since the department was small and the

professors were old and uninterested in undergraduates. There was no mentoring,

advising, or social contact with them or among the students.

MIT had very few female students and faculty.

We had one girl in Aero. I didnít even know her name. Even rarer were black

students. I knew one in the dorm.

Being MIT, there were no humanities courses

to speak of. The typewriter my grandmother gave me got little use. I wrote a

paper on Thucydides Peloponnesian Wars without understanding any part of it.

The only exciting humanities course was about Skinner and involved some library

work at Harvard. MIT had a humanities requirement for graduation. There were

also graduation requirements in athletics and ROTC. These were rightfully

treated as jokes by many of us. In retirement, I took freshman courses in Literature,

Geography, History, Psychology, and Economics at Brookdale Community College in

NJ. Every one of them far superior to any humanities I

had at MIT.

I devoured Science Fiction for recreation.

The Science Fiction Club had talks by Hal Clement and Isaac Asimov. They, along

with Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradberry, and Kurt Vonnegut, were my favorite

authors.

Classical

music was

a big part of life in the Boston area. There were several classical music AM

and FM radio stations. MIT had a station in the dorm basement. My friend Roger

Buck was one of the DJs.

I had built a Heathkit FM radio, one of the

few FM receivers in the dorm. We strung over a mile of army field wire (from

the war surplus store) around the East Campus dorm buildings with several

"audio lines" (connections to individual's amplifier speaker

connection and taps to other student's room audio inputs). I was involved in a

city-wide experiment for stereo audio. We had various arrangements of

microphones in the MIT auditorium broadcasting concerts: one channel on WCRB FM, the other on WMIT AM from our basement,

and using the audio lines. The sound was so spectacularly better that stereo

later became standard for everything audio.

I liked the courses. The subject matter

interested me, and there were many choices and freedom to take classes in other

departments. I specialized in thermodynamics and internal combustion engines.

Junior year was focused on the design of a 2-place twin-jet training plane. I

had my fill of drafting table work after high school and could not get into the

project. The airplane I designed was a real dud and resembled nothing exciting

or advanced. The math associated with the project's aerodynamics, structures,

stability-and-control was beyond me, and I did not do well in those courses.

Pneumonia knocked me out in the middle of

Junior year. I nearly died. Friends walked me over to the MIT Infirmary. After

a week, MIT sent me home for a month. I missed too much of a couple of courses

and had to drop them.

An interesting thing happened in our

class. We got a "Hungarian Freedom Fighter," a victim of the

Russian takeover of Hungary. He was Superman. A bit older, a Hungarian Air

Force fighter pilot and champion glider pilot, accomplished Aeronautical

Engineering student, perfect English, tall, handsome, personable, and the

darling of our professors and the only girl in our class. I was not the only

one to feel inferior.

Fun

Fair

I worked at the Fun Fair in Skokie, IL, near

my home for all three summers. On good mornings, I would go out and fly, then

drive the miniature train, and run other rides in the afternoon and evening,

then pick balls at the driving range at night. I was too depressed and burnt

out to seek better jobs.

MIT Flying Club

The MIT Flying Club owned 2 Cessna 140s, 2-place rag wing 85 HP 100 mph simple

airplanes. These had radios, and we ran them out of Hanscom Air Force Base in

Bedford. It was an exciting place to fly as there were B-50s (later models of

B-29s) and other heavy planes. I did not get much flying time as it was an hour

away by bus, but I enjoyed dealing with the club. I produced the mimeographed

newsletter, was treasurer, and later president of the club. The members of the

club were mostly wealthy grad students and faculty with cars. It was not a

social club. Here is an

interesting article about the club in 1948-1949. How the club is today.

The Little Green

Car

Mom bought me a Renault Dauphine at the start

of my senior year. It was a tiny 4 door car that was fun to drive. It's

not so much fun to keep it running, and difficult to park in Cambridge legally.

In retrospect, it was a big mistake to have it. But I loved driving it. And

fiddling with it (which is what many kids did in high school with hot rods). I

had a couple of dates with a Simmons girl who liked to drive the car. She liked

it, not me.

My senior thesis was on turbo

supercharging the light plane engine, and I worked in the Mechanical

Engineering engine lab.

Senior year was very hard. I was rootless and did not have any idea where I was

headed. I did not want to go on to grad school and

didn't have any idea where I might find a job or build a life.

The 704 Computer

IBM donated a 704 computer to MIT and built a

new building to house it. I had seen many 701s on a field trip to Pratt &

Whitney and was intrigued by them. During my senior year, I signed up to take

the only course MIT offered in digital computing. The arrival of the new

computer created too much excitement, and the class was grossly oversubscribed.

I often had to stand outside the classroom windows on a ledge to hear and see

the instruction. There was no textbook yet. A friend gave me a bootleg copy of

the IBM 701 reference manual, but that was not much use since we had no

computer access, and the course was mostly math. I got an incomplete in the

course and stayed the summer to try and make sense of it. I flunked it. The

only course I failed (I had over a C average). I had dropped some courses in my

junior year and did not have enough credits to graduate with my class. I

had to complete another semester to graduate.

I had a job lined up at Mooney Aircraft in

Kerrville, TX. They were interested in my work on turbosupercharging (years

later, Cessna was the first to offer a turbosupercharger using the same engine

as my paper study). Now, thousands of light airplanes use turbosuperchargers. I

was not disappointed to lose out on the job. I did not want to move to Texas.

My grandfather and mother were incensed that

I did not graduate. I was left with no support or will to continue the pathetic

life I was leading. I did not want to stay another semester and could not

justify wasting more of my grandfather's money. I was pathologically

depressed

since 7th grade and had no business being at MIT.

Next Army